Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButtonImage title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Image title

Untertitel hier einfügenButton

Classification of the Vineyards

The Project of the Century

1892 was an inflection point for German winegrowing. Traditionally, wine had been sold around the world based on its origins. French wine, Bordeaux, Rhine and Mosel. Fine wines were often labeled in combination with the town names, and notably rare high-end wines were also appended with the name of the vineyard. Origin was a synonym for quality. Until 1892, when a new wine law decimated that system. Its focus was on “improvement” and “natural purity.” Did the wine require doctoring with sugared water, or had the grapes achieved sufficient natural sugar and mature acidity? Precise sugar volumes can, to some extent, be determined by the density of the grape juice — leading to the rise of measurements in “degree Öchsle.” Both in winegrowing and in the wine laws, which were perpetually subject to rewriting. The culmination came in the wine act of 1971, which used the grapes’ sugar content to define quality parameters. A vineyard's inherent potential was no longer of interest; its name was important solely for marketing. And to drive those sales, many renowned sites were enlarged... massively. The integration of parcels with heterogeneous geological and microclimate characteristics increasingly pushed the concept of the vineyard as a guarantee for typical tastes — and as a cultural ambassador — into the realm of ad absurdum. And as if this weren’t bad enough, biotechnology soon began its own rise. Yeasts, enzymes & more allowed for whatever taste profile was desired. Origins and varieties mutated into global brands.

By the 1980s, we were already looking for alternatives to this zeitgeist. This meant intensive discussions on questions of the taste of each individual parcel and how to communicate our wines in an effective way.

As a first step, we made the decision in 1984 that henceforth we would ferment the wines fully, foregoing the prädikats such as Kabinett, etc. “Downfall of Mosel wine culture,” sniffed the self-appointed guardians of the grail, while the avant-garde celebrated a ‘new style’. It would take only a few years before the larger public was struck with ennui toward spätlese wines and begin looking at our approach as a model. The template would go on to help dry Mosel wines assume the elite status they currently hold at fine dining establishments worldwide.

But this style of wine is ‘new’ solely for those whose memory of ‘tradition’ runs only back to the years of Germany's ‘economic miracle.’ For centuries, our family fermented the wine completely. It wasn’t until 1961 that fermentation was stopped.

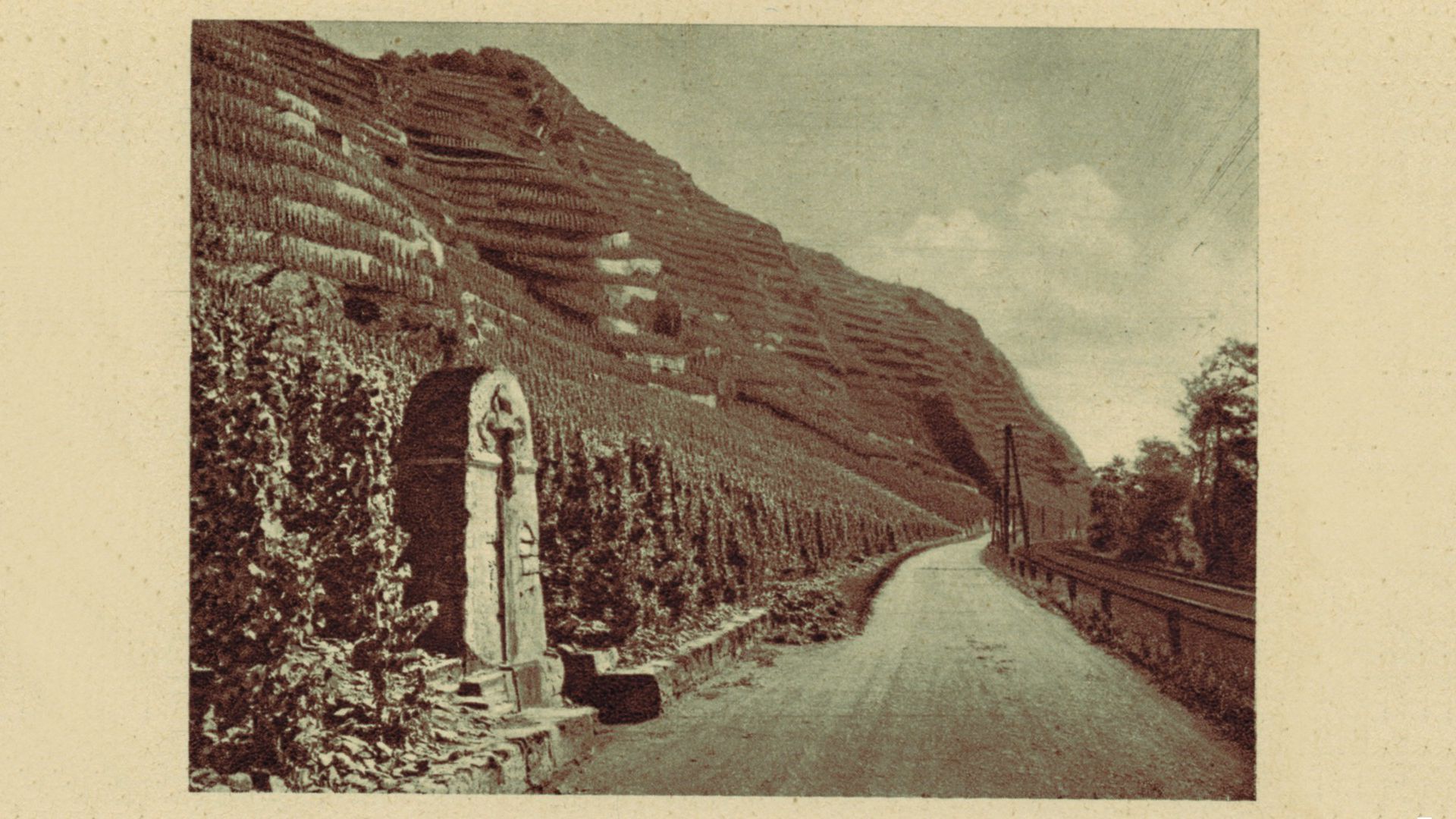

“Dry,” it must be said, is just one aspect of our vision of a Renaissance of classic Mosel wine: how about old vines that are nourished exclusively organically, high plant densities with low vine yields, strict selection of the grapes, extended maceration, vinification using neither yeasts nor enzymes, yet plenty of extended fermentation and wood aging... This is how the unique taste of each individual parcel is conveyed into its wine, and how to give voice to the specific vintage.

But the discussion that then follows is a tricky one. Are vineyards undemocratic? Is there a hierarchy? And if so, is it an objective one or more a cultural gentleman’s agreement?

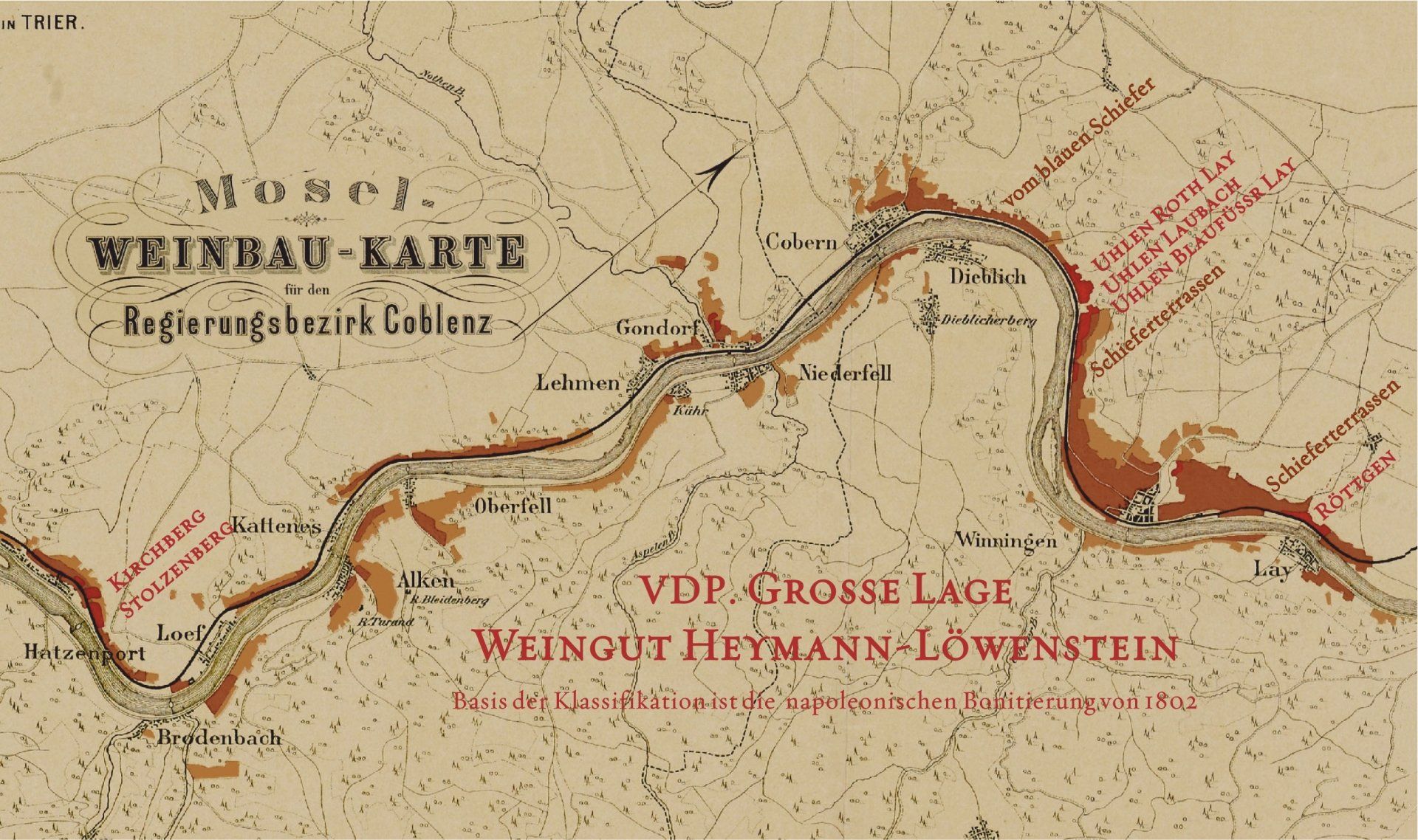

We see it as a matter of taste and tradition. As far back as 1985 we described our best parcels in Röttgen and Uhlen as “grand crus”. As a logical follow-up, all wines that didn’t present a truly significant vineyard character were classified as “premier crus.” When grown in the slate soils of the Devonian layers of the Rittersturz hill, they bear the name “Schieferterrassen” (‘Slate Terraces’); if cultivated in the layers from the Laubach, they are then defined as “von blauem Schiefer” (‘From Blue Slate’).

We quietly let fade a number of site names that, while traditional, said little about their taste. Quite the opposite in Uhlen: Here we observed three characters, each radically different, all subsumed under one name, making it necessary to communicate the identity of the slate using sub-appellations. After many years, we finally succeeded in legalizing this, convincing the EU to allow for official registration of the Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay, Laubach and Roth Lay as “Protected Designations of Origin” (‘geschützte Ursprungsbezeichnungen’ in German). As such, they are the first single sites anywhere in Germany to qualify for the system of Appellations d’Origine Contrôllées, meaning the designation of origin is not — as defined in German law — defined strictly by geology, but rather also by production criteria.

Within the VDP, discussions regarding site classification increasingly circled around a key decision: Should we wait for the law to adapt, or take our fates into our own hands? After long deliberations, we ultimately decided on the latter and in 2012 ratified a VDP-internal classification system for our vineyards as well as a communication model for the wines. It has since gone on to shape German quality winegrowing, and looms large in the ongoing revisions to the German Wine Act.

- Classification of VDP Sites

VDP Quality Pyramid

Taking the Burgundy system as its model, both quality and a strict set of requirements in both vineyard and cellar are applied from regional and village-level wines to the “Premier” and “Grand Crus”.

VDP – GROSSE LAGE the extraordinary peak - strongly evident site character

VDP – ERSTE LAGE quality with significant site character

VDP – ORTSWEIN the better vineyards - with a clear profile

VDP – GUTSWEIN the foundation - this is where the fun starts

Flavor profiles

Wines in Germany were traditionally produced not just as dry. An indication of the taste profile is thus warranted, and the ‘old’ terms can be insightful.

The full-bodied quality wine is, when declared by the wine law to be dry and originating from a VDP.GROSSE LAGE, defined as a Grosses Gewächs.

The delicately fruity Kabinett

tastes airily light, with barely perceptible natural sweetness and a low alcohol content

The elegant Spätlese

is shaped by the sophisticated play of fine natural sweetness, especially in youth

The honeyed Auslese

is additionally graced with fine Botrytis notes, especially in its Goldkapsel, Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese variants

The Varieties

The possibilities are wider at the Gutswein and Ortswein levels. At the tip of the quality pyramid, only a region's traditional varieties may be used.

Outlook

Winningen Uhlen Laubach VDP-Grosse Lage Grosses Gewächs? The correct formal description for our dry wines from the Uhlen is, from a semantic standpoint, not only a tautology, but also a communicative non-starter. The idea that the top dry wine from a top site should be a Grosses Gewächs — thus glorifying a wine type instead of the vineyard as a “grand cru” — has never sat right with us. Unfortunately, our viewpoint wasn’t the one that won out. And then the GG became a huge hit anyways! The chances that this “industrial accident of a classification” will be done away with appear poor.

Grosses Gewächs, Kabinett, Spätlese, Auslese... What vineyard can express its site character in all of these flavor variants? The assignment of Grosse Lage sites to flavor profiles is yet another hard nut that needs cracking. Another few years of discussion and wrestling out “gentlemen's agreements” will be required until we find a clear way of communicating terroir.

Thank you for bearing with us. Over 100 years of Öchsle simply refuse to ferment quickly into terroir.

- the Protected Designations of Origin on the Uhlen

Asterix in China

Forms? First they needed to be designed. The officials in Brussels initially approved of them, then disapproved, then reworked them and had them translated (incorrectly); then the institution in Brussels was restructured, putting everything on hold, and then the application was officially tossed; it was then refiled and rejected on content grounds; revised, improperly translated again, pushed onto the waiting list... the High Commissioner promised quick treatment multiple times, the Commission is massively overloaded and understaffed. Ugh.... But then:

the first “Appellations contrôlées” for German single sites!

They are based on

• a precise geological delineation by the State Office for Geology

• strict guidelines in the vineyard (only Riesling, plant density of at least 7000 vines/ha)

• Yield limitations to 70 hl/ha of cadastral area (corresponds in reality to 50 hl/ha given the existing inclines of over 100 %).

• ambitious maturation parameters (at least 88 degrees Öchsle or max. 7.5 % acidity)

• traditional vinification (ban on ‘new enological processes’)

• definition of taste profiles (only dry/off-dry and nobly sweet)

• clear communication (no Kabinett, no Spätlese)

Uhlen facts and figures:

1.58 ha Blaufüßer Lay

6.94 ha Laubach

8.27 ha Roth Lay

16.79 ha total

Wine> The classification of the vineyards

The classification of the vineyards

the project of the century

1892 was an inflection point for German winegrowing. Traditionally, wine had been sold around the world based on its origins. French wine, Bordeaux, Rhine and Mosel. Fine wines were often labeled in combination with the town names, and notably rare high-end wines were also appended with the name of the vineyard. Origin was a synonym for quality. Until 1892, when a new wine law decimated that system. Its focus was on “improvement” and “natural purity.” Did the wine require doctoring with sugared water, or had the grapes achieved sufficient natural sugar and mature acidity? Precise sugar volumes can, to some extent, be determined by the density of the grape juice — leading to the rise of measurements in “degree Öchsle.” Both in winegrowing and in the wine laws, which were perpetually subject to rewriting. The culmination came in the wine act of 1971, which used the grapes’ sugar content to define quality parameters. A vineyard's inherent potential was no longer of interest; its name was important solely for marketing. And to drive those sales, many renowned sites were enlarged... massively. The integration of parcels with heterogeneous geological and microclimate characteristics increasingly pushed the concept of the vineyard as a guarantee for typical tastes — and as a cultural ambassador — into the realm of ad absurdum. And as if this weren’t bad enough, biotechnology soon began its own rise. Yeasts, enzymes & more allowed for whatever taste profile was desired. Origins and varieties mutated into global brands.

By the 1980s, we were already looking for alternatives to this zeitgeist. This meant intensive discussions on questions of the taste of each individual parcel and how to communicate our wines in an effective way.

As a first step, we made the decision in 1984 that henceforth we would ferment the wines fully, foregoing the prädikats such as Kabinett, etc. “Downfall of Mosel wine culture,” sniffed the self-appointed guardians of the grail, while the avant-garde celebrated a ‘new style’. It would take only a few years before the larger public was struck with ennui toward spätlese wines and begin looking at our approach as a model. The template would go on to help dry Mosel wines assume the elite status they currently hold at fine dining establishments worldwide.

But this style of wine is ‘new’ solely for those whose memory of ‘tradition’ runs only back to the years of Germany's ‘economic miracle.’ For centuries, our family fermented the wine completely. It wasn’t until 1961 that fermentation was stopped.

“Dry,” it must be said, is just one aspect of our vision of a Renaissance of classic Mosel wine: how about old vines that are nourished exclusively organically, high plant densities with low vine yields, strict selection of the grapes, extended maceration, vinification using neither yeasts nor enzymes, yet plenty of extended fermentation and wood aging... This is how the unique taste of each individual parcel is conveyed into its wine, and how to give voice to the specific vintage.

But the discussion that then follows is a tricky one. Are vineyards undemocratic? Is there a hierarchy? And if so, is it an objective one or more a cultural gentleman’s agreement?

We see it as a matter of taste and tradition. As far back as 1985 we described our best parcels in Röttgen and Uhlen as “grand crus”. As a logical follow-up, all wines that didn’t present a truly significant vineyard character were classified as “premier crus.” When grown in the slate soils of the Devonian layers of the Rittersturz hill, they bear the name “Schieferterrassen” (‘Slate Terraces’); if cultivated in the layers from the Laubach, they are then defined as “von blauem Schiefer” (‘From Blue Slate’).

We quietly let fade a number of site names that, while traditional, said little about their taste. Quite the opposite in Uhlen: Here we observed three characters, each radically different, all subsumed under one name, making it necessary to communicate the identity of the slate using sub-appellations. After many years, we finally succeeded in legalizing this, convincing the EU to allow for official registration of the Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay, Laubach and Roth Lay as “Protected Designations of Origin” (‘geschützte Ursprungsbezeichnungen’ in German). As such, they are the first single sites anywhere in Germany to qualify for the system of Appellations d’Origine Contrôllées, meaning the designation of origin is not — as defined in German law — defined strictly by geology, but rather also by production criteria.

Within the VDP, discussions regarding site classification increasingly circled around a key decision: Should we wait for the law to adapt, or take our fates into our own hands? After long deliberations, we ultimately decided on the latter and in 2012 ratified a VDP-internal classification system for our vineyards as well as a communication model for the wines. It has since gone on to shape German quality winegrowing, and looms large in the ongoing revisions to the German Wine Act.

- The classification of the locations in the VDP

VDP Quality Pyramid

Taking the Burgundy system as its model, both quality and a strict set of requirements in both vineyard and cellar are applied from regional and village-level wines to the “Premier” and “Grand Crus”.

VDP – GROSSE LAGE the extraordinary peak - strongly evident site character

VDP – ERSTE LAGE quality with significant site character

VDP – ORTSWEIN the better vineyards - with a clear profile

VDP – GUTSWEIN the foundation - this is where the fun starts

Flavor profiles

Wines in Germany were traditionally produced not just as dry. An indication of the taste profile is thus warranted, and the ‘old’ terms can be insightful.

The full-bodied quality wine is, when declared by the wine law to be dry and originating from a VDP.GROSSE LAGE, defined as a Grosses Gewächs.

The delicately fruity Kabinett

tastes airily light, with barely perceptible natural sweetness and a low alcohol content

The elegant Spätlese

is shaped by the sophisticated play of fine natural sweetness, especially in youth

The honeyed Auslese

is additionally graced with fine Botrytis notes, especially in its Goldkapsel, Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese variants

The Varieties

The possibilities are wider at the Gutswein and Ortswein levels. At the tip of the quality pyramid, only a region's traditional varieties may be used.

Outlook

Winningen Uhlen Laubach VDP-Grosse Lage Grosses Gewächs? The correct formal description for our dry wines from the Uhlen is, from a semantic standpoint, not only a tautology, but also a communicative non-starter. The idea that the top dry wine from a top site should be a Grosses Gewächs — thus glorifying a wine type instead of the vineyard as a “grand cru” — has never sat right with us. Unfortunately, our viewpoint wasn’t the one that won out. And then the GG became a huge hit anyways! The chances that this “industrial accident of a classification” will be done away with appear poor.

Grosses Gewächs, Kabinett, Spätlese, Auslese... What vineyard can express its site character in all of these flavor variants? The assignment of Grosse Lage sites to flavor profiles is yet another hard nut that needs cracking. Another few years of discussion and wrestling out “gentlemen's agreements” will be required until we find a clear way of communicating terroir.

Thank you for bearing with us. Over 100 years of Öchsle simply refuse to ferment quickly into terroir.

- the Protected Designations of Origin on the Uhlen

Asterix in China

Forms? First they needed to be designed. The officials in Brussels initially approved of them, then disapproved, then reworked them and had them translated (incorrectly); then the institution in Brussels was restructured, putting everything on hold, and then the application was officially tossed; it was then refiled and rejected on content grounds; revised, improperly translated again, pushed onto the waiting list... the High Commissioner promised quick treatment multiple times, the Commission is massively overloaded and understaffed. Ugh.... But then:

the first “Appellations contrôlées” for German single sites!

They are based on

• a precise geological delineation by the State Office for Geology

• strict guidelines in the vineyard (only Riesling, plant density of at least 7000 vines/ha)

• Yield limitations to 70 hl/ha of cadastral area (corresponds in reality to 50 hl/ha given the existing inclines of over 100 %).

• ambitious maturation parameters (at least 88 degrees Öchsle or max. 7.5 % acidity)

• traditional vinification (ban on ‘new enological processes’)

• definition of taste profiles (only dry/off-dry and nobly sweet)

• clear communication (no Kabinett, no Spätlese)

Uhlen facts and figures:

1.58 ha Blaufüßer Lay

6.94 ha Laubach

8.27 ha Roth Lay

16.79 ha total